Sketch Fridays #14 – Lemmy, et al.

Celebrities die every day. They only seem to go unnoticed because their celebrity is limited to a specific segment where the loss is tangible among those fans even if the ripple doesn’t reach the greater culture.

Since January started, the deaths of (at least) three celebrities caused a glut of captioned pictures, fan art, and 140-character eulogies across the internet. Surely, people in modern American culture exist who do not know who Lemmy Kilmister, David Bowie, and/or Alan Rickman were, but what ostensibly makes their deaths different is that their popular reach spread across multiple fandoms and media.

I was not necessarily more familiar with one over the rest; I would, in fact, argue that I was reasonably detached from all three of them and don’t profess any specific idolatry. Mostly, they were names filed into my pop culture registry, whose facts and biographies and philosophies I acquired over time but to whom I declared no allegiance. The trio is a fascinating cluster if only because, through a certain lens, they are all singular personalities instantly recognizable.

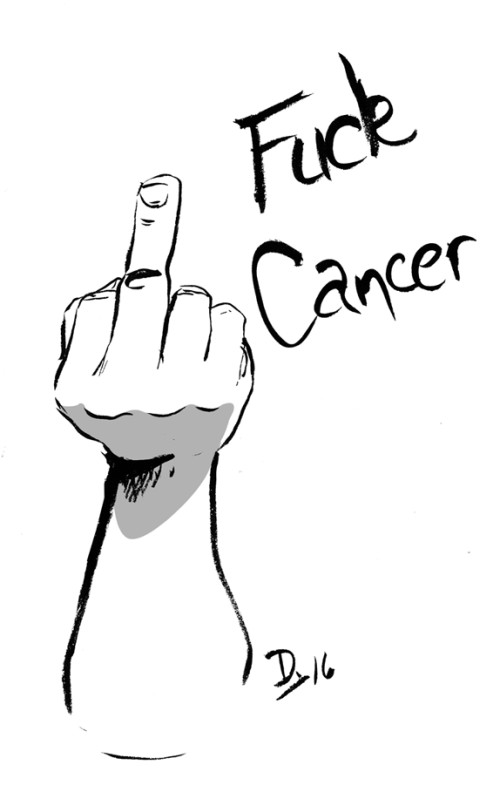

Lemmy, and his heavy metal/hard rock band Motörhead (ignore the umlaut), became known as a heavy metal stalwart because, from start to finish, he made the same music. Rather than viewing that as a deficit, in the metal community it means that he’s dependable. Listeners often go to metal as a form of release and, believe it or not, as a way to calm down and center themselves. It’s raw nerve rendered as volume and every aspect of the music––from instrumentation to lyrics to vocal stylings––work together to create a safe place to release the dark thoughts or simple bad moods we all feel. It’s unity through extended middle fingers pointing outwards.

Through the heavy metal din, Lemmy became a bedrock for the genre because any time a Motörhead album came out, you knew exactly what you were getting. Even though he dallied with acoustic music or as a songwriter for Ozzy Osbourne (or, more recently, as a member of a heavy metal army in the interesting Double Fine video game, Brütal Legend––again, ignore the umlaut), his stamp was always visible on anything he touched. Likewise, his persona was carved in stone and that became a point of solace for not only many fans, but musicians as well. Despite being gruff in personality and appearance, it was widely known that he was generous with his fame and efforts for up and coming musicians and his dedication to them––even when their fame peaked and fell––sealed his place as the heavy metal godfather.

David Bowie, of course, superficially represents the exact opposite of everything Lemmy stood for. However, the mercuriality of Bowie became his defining characteristic––we expected it, wanted it, and he always changed. Despite the constant ch-ch-changes (sorry), there was always an edge that poked through the veneer––perhaps it was his signature eyes, or the angularity of his features, his voice, or his songwriting––but as much of a chameleon Bowie was, what he always made evident was that he was making this change for a reason. He used the variety of media at his disposal because it was the right way to say what he needed to say. In that way, he became dependable as a consummate performance artist.

As discussed on the most recent episode of my podcast, Bowie was probably the artist (of the three) with whom I was least familiar. I knew a lot about him and his career, but was never a consumer of it aside from his role as the Goblin King in Labyrinth and his music used in the recent video game, Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain. (Oh, and “Let’s Dance” because it started the career of Stevie Ray Vaughan, and “Under Pressure” because Queen is rad.) Despite that, even I could hear the Bowieness of a song I’d never heard before, and the throughline is clear from Labyrinth to his collaborations with Nine Inch Nails even if it sounds like a completely different person at the microphone. It is just clear.

Of the three, Alan Rickman probably has a place in many people’s hearts more out of nostalgia than anything else. Fans of Die Hard are evangelical about the movie and hold up Rickman as the patron saint of action movie villains based on his portrayal of Hans Gruber. More recently, of course, he is beloved as the tragic Severus Snape from the Harry Potter film franchise. Within my walls, he is remembered for his turns in Dogma (as the Metatron, the voice of God) and Love Actually (where, coincidentally, he played a character named Harry).

Despite the variety of roles he brought to life, he never really “disappears” in the way that we describe some character actors. His intrinsic presence is too powerful––every angle on his face points down, his voice destroys subwoofers in homes across the world, there is an ache of sarcasm that sits on his shoulders––that it’s less that his characters are memorable and more that he is. I don’t mean to diminish his ability––he continues to be amazing to watch on screen––but like many actors out there, he transcended his profession and became “Alan Rickman.” People do impressions of Rickman, not of Snape or Gruber (or the Sheriff of Nottingham––holy cow, he was great in that movie).

What I’m arguing is that these three stand out in their deaths because they were more than just the roles they played, so to speak. Something set them apart from their work and it became more about finding the “them” in their work almost more than appreciating the work itself. And while that was surely not their goal––perhaps they would have derided such an assessment––what inevitably links the three is that there are truly no imitators out there.

Oh and this:

Discussion ¬