Growing up a reader of superhero comics, I’ve noticed fans tend to relish in the practice of categorization. This is endemic to many fandoms (if not all), and a lot of this categorization is defined with the superlatives of “Best” or “Favorite,” things that will drive a young fan’s passion and, when older, looks quite silly in hindsight.

Because superhero comics are character-driven, we have the pleasure of seeing multiple artists tackle the same character filtered through individual styles. For fervent fans, this conversation usually can be as civil as a Rogerian argument or as vitriolic as a cable news analysis panel, but, through calmer eyes, I find it fascinating how artists translate the symbols of a character into something uniquely their own.

I’m pretty sure that upon first glance, Wolverine became my favorite character in the X-Men (though I am a staunch Cyclops apologist as well). I had a lot of anger issues when I was young (still do, but I’ve learned to manage those tendencies much better), and Wolverine crouched (and grimaced) as a kind of self-help guide to how to deal with that kind of problem. He had a short fuse, he had problems making (and keeping) friends, but he was also a hero. Despite his anger, he used it to do good, even if it made a mess in the process.

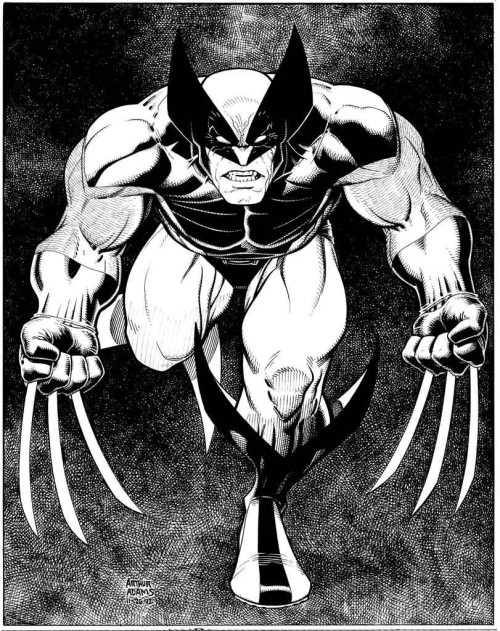

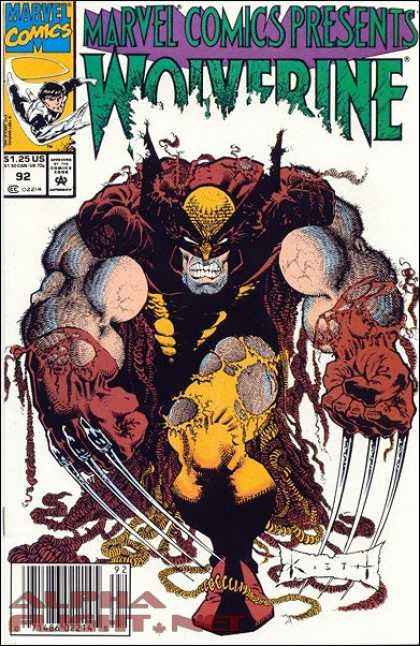

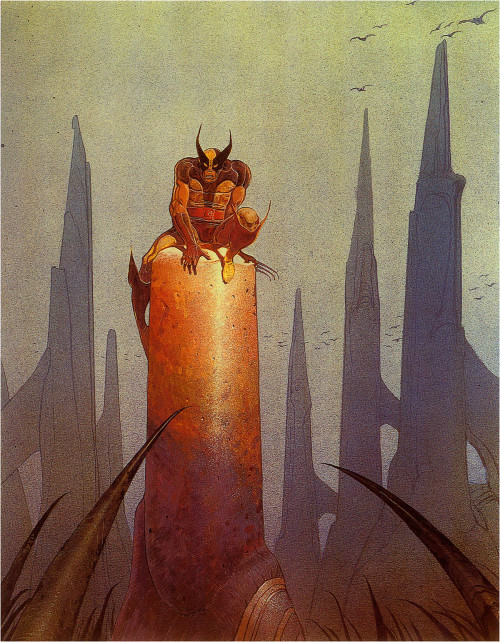

There are a few requirements for Wolverine, but are prioritized around the iconographic aspects of his costume and superpowers: the pointy mask, the claws, and––if unmasked––his pointy hair. Secondly, his small stature, hairy arms, and costume choice (he’s had several, though for those in the know––and as is evident by my choice of images and my own drawing––his “brown and tan” costume is my favorite) tend to be recognizable milestones that are more malleable. Though that seems like a pretty rigorous checklist, there is quite the range for exaggeration and interpretation that artists can weave through those eyelets.

My tastes are always in flux, but I often wonder what “my” Wolverine (or Batman, etc.) would be. Right now, I like the compact frame and the restrained wings of the mask. The way the movies reinterpreted how his claws worked really impressed me and I feel compliment his personality and general approach to conflicts rather well. I tend toward a practical approach to costuming, though I couldn’t resist the wings on the boots, if only to echo the mask. But, I still try to include visible seams and I don’t particularly like to see individuated muscles or ligaments through the fabric, though I pushed that limit a little bit.

Though I haven’t looked at a Wolverine or X-Men comic in almost ten years (aside from Old Man Logan and the first volume of Astonishing X-Men), it seems now that the interpretations of the character seem to vacillate between Wolverine as raging animal, hulking brute, or grumpy drunk. Like all characters in the X-Men, being representatives of the Other and just wanting acceptance in a world that shuns them, I prefer to approach Wolverine from a humanistic perspective––he’s a person first, clawed maniac second (and even then, I would prefer to keep the homicidal rages as a thing of myth rather than actual habit). Perhaps it’s because I find a lot of his “faults” in line with my own, what I want is to see a heroic figure that shows that even angry people––with a little work––can be normal and functional; that the anger, rather than simply being a quality that ostracizes, is as much a tool as his claws and heightened senses to be used to help rather than harm.