To date, I am pretty sure I have only officially accepted two commissions. I’m not counting the pro-bono theme music I wrote for a podcast, either. I’m not talking about sketches done at a show or something like that, but a process-based approach to a publishable final product. I don’t like commissions because I don’t like working for other people, as I’ve discussed before. Part of it may be arrogance, no doubt, but a more likely reasoning (though just as flawed) is that I don’t like the idea that I could let people who are about to pay money to me down with a subpar product. But I have been making strides to be more confident; however, that doesn’t mean I have started taking random commissions, it means that to my closest friends, I might start saying yes.

I have issues with anxiety. I don’t think it’s the same anxiety you see people writing about on the internet. Ironically, introverts are some of the loudest people on the internet with regard to bold declarations of introvert-pride and catenated lists of “how to treat” introverts. A lot of those lists revolve around social anxiety, that if in a crowd for too long they just start to freak out. As an introvert, I think I have that to some degree, but I’ve been able to mitigate it over the years to the point where being among groups and crowds don’t bother me; they just don’t energize me. The anxiety that plagues me is usually related to an imposter syndrome I’ve dealt with since starting graduate school and has continued into my career.

With regard to commissions, one of the most stressful things for me is likenesses. I remember early in Eben07‘s run, we had a table at a local event and we thought it would be a good idea to sell sketches. Of course, I hadn’t prepared for the inevitable couple to come up to the table, hand over five dollars, and asked if I could draw them. I burst into a flop sweat, looking down at the blank sketch card and back up at the pair, silently wondering how the hell I was going to make some cartoony drawings look like the two strangers before me. I took cues from hairstyles and clothing, hanging them on fairly generic figures I could quickly get onto the page. They smiled, thanked me and walked away, ecstatic that the ordeal was done, but worried that they would come back after a second look, offended and demanding recourse for such a travesty. With luck, they never returned.

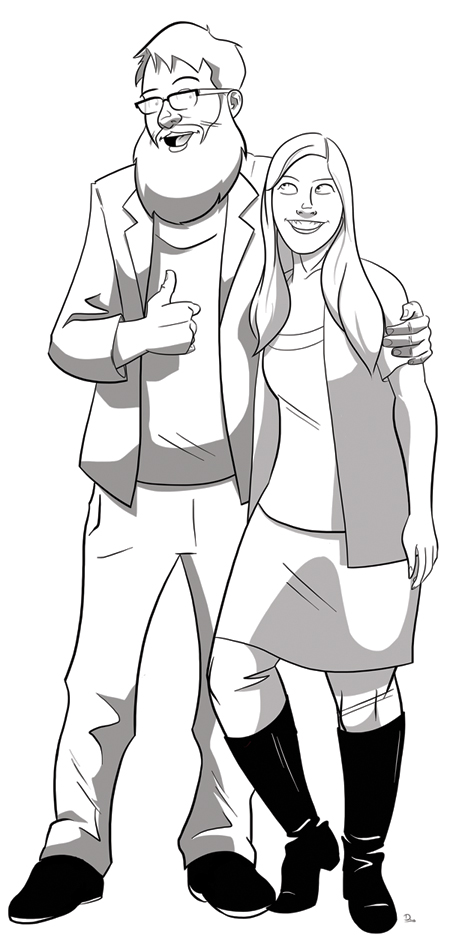

Recently, I was asked by good friends, Eben and Jessica, to make a drawing of them for their upcoming wedding. Of course I agreed; who wouldn’t? Even though I am quite a bit more confident in my abilities, I was still a bit nervous at attempting their likenesses. I wanted to have a balance between what they actually look like against my cartoony style––especially as it was during Eben07. It was fun to put together, an amalgam of my own style and various photographic reference, I shaped and molded the figures before I put down the final lines. The final image is in full color, but in keeping with the tone of the other Sketch Fridays, I figured I’d post the line art and shading instead (save the full color image for the wedding itself). Surprisingly, I’m very happy with the result (as are they, thankfully).