Going to APE was a big deal for me and Long John.

When I first went to APE, back in 2010 with my previous comic, it made such an impression on me that its memory eclipses the larger cons I attended since as an exhibitor. APE was a convention known to have a very specific atmosphere, a “vibe”, one that was casual and copacetic to independent-minded creatives who were given a weekend to be treated like they were the only ones making entertainment on this planet. Such were the sentiments I walked away with after my first attendance as an APE exhibitor and were solidified in the subsequent shows I attended.

So, once I started Long John, there was a far-off dream of returning to APE. In that interim, a lot of changes happened to APE that many maligned. Undeterred, I stuck with the goal so that, this year, I applied and was accepted to be an exhibitor. After much anticipation, and after walking in, it was a very different first impression than my previous experiences with the show.

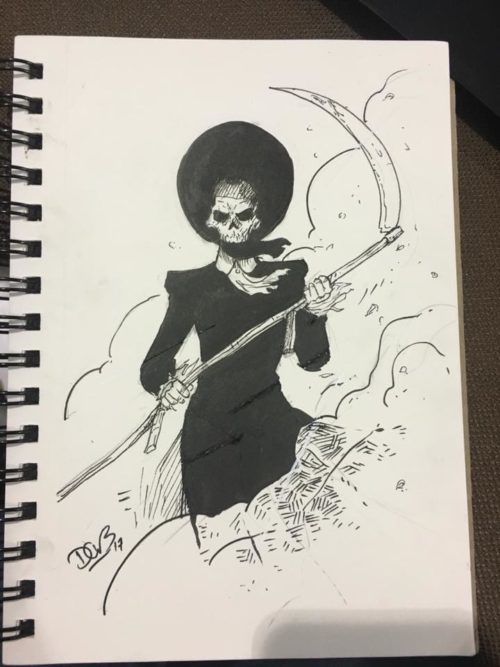

A Hellrider Jackie sketch to kick off APE 2017.

Firstly, it had moved from hip-nexus of San Francisco and its Concourse Exhibition Center (RIP) to San Jose and its Convention Center’s South Hall, which is a large, permanent tent with a rigid skeleton to keep it aloft. However, once I walked through the majority of this huge, empty hanger to the exhibitor registration table and into the show floor proper, I felt immediately at home.

Secondly, it was much smaller than my last attendance, five years prior. The vendors present, however, were much in-line with what I saw at APEs previous––independent, bootstraps-pulling creators doing their best to make the best products they can (of whom I count myself among). Though it was smaller with lighter attendance, it still felt––at its core––like APE, and that was enough to keep me inspired and loyal to the show.

If anything, the show reminded me of why I love Crocker Con or this year’s inaugural Sacramento Indie Expo––it feels like getting in on the ground floor of something special. To some, it feels less like the starting point of something new and more like a death knell to a once-great show, but I prefer to focus on the former because it could be as great as it ever was with the right marketing and support from not only the organizers of the show, but of the exhibitors.

Though it was a lightly attended show (especially Sunday––woof), most people who turned up were ready to spend money to support independent creators, resulting in the most profitable show I’ve ever done. With that in mind, I have no grounds on which to complain, but I see the valid points the detractors are making and I think the steps to make it a bigger and more visible event are probably pretty easy. With hope, the organizers listen and rally next year to help the rest of the creative community see APE like it looks to me: a place for independent creatives to thrive, share, and succeed.