If webcomics allow for anything, they allow for experimentation with medium, format, delivery, etc. I’ve mentioned many times that Long John is, at least, partially about me pushing myself, creatively. However, that doesn’t exclusively mean challenging myself as a visual artist.

Long John is a single story, but there are and will be a lot of characters who have stories that won’t be told during the course of the main narrative. That’s par for the course when it comes to sticking to a story, but having those characters and their stories in mind is what helps make the main narrative stronger.

One of those characters is the Hellrider––she calls herself ‘the Hellrider’, townsfolk call her ‘Hellrider Jackie’––who is heavily featured in the opening scene of Long John. She is an overarching enigma of the story and the one bit that, at first, doesn’t seem to fit quite right in the world of Long John. One thing that’s clear is that she sees the world in a very different way than normal people do, and that vision is going to be very influential on the unfolding of Long John’s events.

So, with that in mind, part of the Long John updates are going to include side-long glances into Hellrider Jackie’s world.

There’s one problem. I can’t do it. In my head, looking through Jackie’s eyes reveals such a twisted and surreal world––one that allows her to feel justified in her actions (which you’ll learn about soon)––that any attempt on my part wouldn’t come close to how it should look.

Luckily, I know someone who can.

Josh Tobey is an Oregon-based (formerly of Denver) Symbolist painter and illustrator that has been my closest friend for almost twenty-five years (having become friends in the sixth grade). He––along with my relatively new hobby of reading superhero comics––was the reason why I started drawing, actually. Since that time, we have grown as artists, but have done so separately and in unique and distinct directions. He is the definition of a Fine Artist, and through his work I became a more thoughtful artist in my own right. He puts everything of himself into his work; every daub of paint, every representative item on the canvas means something.

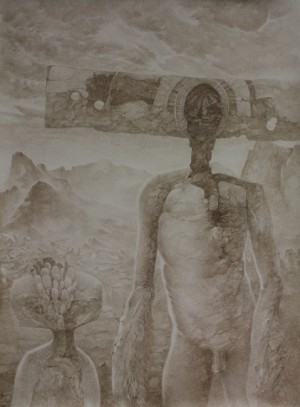

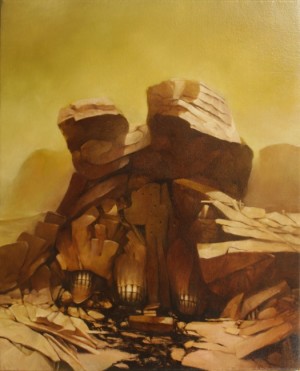

To describe his art is a daunting task because it speaks so much for itself. Some common descriptors are dark, disturbing, frightening, hellish, or apocalyptic. Perhaps just weird. His list of like-minds runs a wide gamut, from Yoshitaka Amano to H.R. Giger to Wayne Barlow to Zdzislaw Beksinski. Josh’s paintings are nightmares of flesh and earth in repose, doomed to wander a hostile and lonely, but quiet, environment during our waking hours. His paintings are perpetual twilight, when our vision is at its worst but our imagination at its most active, squinting from the sun looking for friends or foes and fearing the worst.

Josh was the first person I went to when I was thinking about doing Long John, and his support and enthusiasm are a major reason why it happened at all; but he’s also a major reason why this comic takes so much effort, and each page means so much to me, because I’ve seen the effort––technically, philosophically, and critically––he puts into his work. Because of him I wanted Long John to be Art in the purest, most expressive sense.

Possibly because of all the effort he has put into expressing himself in paint, he hasn’t really thought about comics as a medium for his own artistic expression since high school. However, I have dragged him into the fray after pitching him to be the dedicated Hellrider Jackie artist.

What I mean by that is that at the conclusion of “Chapter 1: Sunza,” you’ll be subjected to a four-week excursion into Hellrider Jackie’s morally obscure world that, to her, is literally being consumed by rot and char. When I realized I couldn’t pull off the visuals I wanted to have on the page and still have them be evocative, interesting and challenging for the reader, Josh immediately popped into mind. I was hesitant at first because he wasn’t really pursuing comics, but as the idea for a Jackie side-story grew in my mind––and I knew I couldn’t achieve what I wanted to achieve––I reached out. To my surprise, he agreed.

Josh and I became artists together, but went our separate artistic ways early on. Even though his work is vastly different than my own, his work has inspired mine on multiple occasions. He is one of my most favorite artists alive, and deserves any exposure he can get and that I can provide. Despite the aesthetic differences, our goals have always been the same––to express Art that has truth, meaning, biography, commentary, and story. I have wanted to work with him in some capacity, but the disparateness of our chosen media (and geographical distance) has never really presented an opportunity, until now.

So, please know that what you see through Josh’s hand (and, simultaneously, through Hellrider Jackie’s eyes) are what I saw even before he put ink to page. Had I done her story myself, I would have just been working from the mental image of how Josh would have drawn it and failed miserably. If Josh’s art is anything, it’s a challenge to a viewer, daring you to look away, but that’s what makes him the perfect guide for us through Hellrider Jackie’s world.