One of the first artists I was introduced to through popular culture was one whose name I didn’t know for a few good years. Naturally, for nerds of my generation, it was an artist for a video game. Being that this artist was a concept illustrator for a Japanese-developed video game during the reign of the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), credits weren’t readily given lest the player strengthen his or her resolve and beat the game.

My original copy of Final Fantasy (1)’s instruction book.

Yoshitaka Amano is a Japanese artist who rose to fame as the illustrator and cover painter for Vampire Hunter D, a series of popular fantasy novels published in Japan (and crudely translated into English about a decade ago). At some point, he was hired by Squaresoft––a video game publisher––who was at the end of their ropes, fiscally. They figured they could make one last game and, were it good, it would save the company or, were it bad, it would sink it. They decided a turn-based, fantasy role-playing game would be the game to make. As a jest, because of their dire financial straits, they dared to name this game Final Fantasy because, quite literally, it could have been. Amano was hired to do conceptual art, character and creature designs. Though heavily digitized to work with the limited 8-bit, 25-color (at a time) NES, Amano’s very unique style––flowing, dream-like, organic––still came through in the game. It even became more prominent with the release of the Super Nintendo and Final Fantasy IV and Final Fantasy VI (originally released in North America as Final Fantasy II and Final Fantasy III, respectively). Though I didn’t realize it was also Amano at the time, but the popular fantasy anime, Vampire Hunter D (based on the novels), had become a favorite movie of mine as well (just to be clear, both Josh and I were figuring out this mystery together).

It’s safe to say aspects of Amano’s Vampire Hunter D art influenced Hellrider Jackie.

While on a trip visiting San Francisco in the mid-nineties, I somehow ended up in a Japantown bookstore. While there, I found a published collection of Amano’s work, called Maten (translated, it means “evil universe”), that had some of his Vampire Hunter D illustrations (all figured out through good guesses and conjecture, the book was completely in Japanese). The book was published long before he did his Final Fantasy work, and I don’t exactly remember when Josh and I put this book (and his Vampire Hunter D work) together with his Final Fantasy work, but that book became an artistic bible for us; however, for me it was more about learning to appreciate Amano’s aesthetic––what it can do and mean––rather than trying to figure out how it was done.

My meager collection of Amano books.

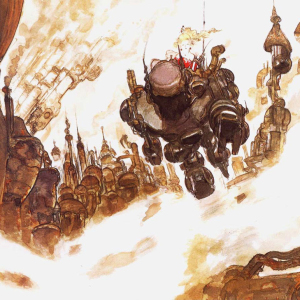

Amano’s work became hugely influential for Josh and me, though it has since manifested in our art in different ways. For me, though my style carries little evidence of his influence, his art really opened up my idea of what illustration could be. Being a big fan of the hey-day of American illustration with the stylized but realistic oils of people like N.C. Wyeth, Howard Pyle, and J.C. Leyendecker, Amano was anything but that norm, but he was doing the same thing. All of them capture the essence of character, scene, and story in a single image, giving the reader a primer for the world created in the mind as a story is read (or played). This is especially helpful for the games of the NES and Super NES era when graphics––though improving––were still primitive and representative unable to generate the veracity of modern gaming machines.

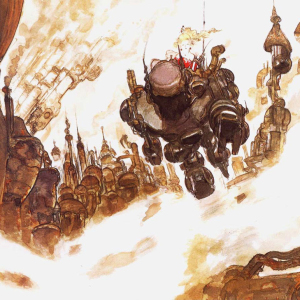

Final Fantasy VI’s opening scene.

Amano’s interpretation of the same scene.

According to Amano, traditional narrative illustration could also have elements of the surreal, of the abstract, of the impressionistic. Rather than simply being literal representations of clothing, scenes from novels, or magazine covers, illustration could have interpretive value, even if that meaning is hard to figure out or even uncomfortable to look at. The best way to describe Amano’s influence on my work and how I approach art is through a series of promotional materials he created for his first exhibition in New York. A series of prints highlighted the name of the show, “Think Like Amano,” with each carrying a different absurdist tagline. I spent too much money and got a full set of the prints, and I ashamedly admit that they sat in a tube for over a decade (last year, one finally got framed and is now proudly hanging in my office at CSU, Sacramento).

The framed “Think Like Amano” print hanging in my office.

The hooks of Amano’s work, for me, is that it is incredibly out of time and place. For a Japanese artist working in the Japanese gaming and animation industry in the 1980s and 1990s, I’m sure he felt, if not the pressure, the presence of what is ostensibly the “industry style” that most Americans consider to be “anime”: big eyes, big heads, spiky hair, lithe bodies and hip clothing. Were I to place an Amano print in front of someone who had no idea about Amano or Final Fantasy (Amano was also the character designer on the classic anime series, Gatchaman, which has been released in America as both Gatchaman as well as Battle of the Planets and G-Force) I would bet the viewer would not be able to tell me the art’s country of origin. As influenced by Alan Lee as he is Gustav Klimt, Yoshitaka Amano instilled in my developing brain that just because you’re working in a specific time, culture, and genre doesn’t mean you have to follow the expected rules of imagery and storytelling.