Mind in the Gutters – Rock & Tin

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

“Mind in the Gutters” is a space for D. Bethel to discuss specific comics without any particular relevance or connection to Long John itself. This discussion covers Tom Dell’Aringa‘s webcomic-first graphic novel, Rock & Tin.

The science fiction genre, despite being a fractal comprising infinite subgenres, has the benefit of providing creators with a toolset to tell meaningful stories about society through the lens of speculative fiction, where we can fantasize about what the world could be, should be, or––if we want to frighten ourselves––will be without proper intervention. It allows people to build a huge world (or galaxy, or universe) in which a genuinely human story can be told, even if it doesn’t use humans to do it.

Such is the conceit of Tom Dell’Aringa’s latest webcomic-turned-graphic novel, Rock & Tin, an all-ages sci-fi fable that manages to have fun while asking some really interesting and tough questions about identity. If this seems a bit at odds with an all-ages comic, I wouldn’t disagree, but the fact that this is a story meant to run the gamut of the literate readership, I applaud him for breaking the false equation most people make by thinking “all-ages” means “only for children.” What comes to mind for producers of actual all-ages stories is, of course, Pixar, whose movies definitely find the balance of appealing to audiences both young and adult. There is no doubt that the Pixar ideal is the mark for which Dell’Aringa is aiming and does an admirable job of hitting. There is a tension in the book, however, that pushes apart theme and story, caused by the very foundations of what makes science fiction great, though it doesn’t necessarily damage Rock & Tin overall as it is a fun reading experience with great art and solid sequential storytelling (i.e., Dell’Aringa knows what he’s doing and it shows).

In the interest of full disclosure, Tom and I have a tangential history in the world of webcomics. He started his previous and first webcomic, Marooned, around the same time Eben and I started up our previous and first webcomic, Eben07, so I consider Tom part of my “class” of comickers (in the school sense: Eben07 started in September 2007, Marooned in March 2008). A lot of us have fallen away over the years, so I’m interested and invested in seeing those that are still around push forward with their ideas and art.

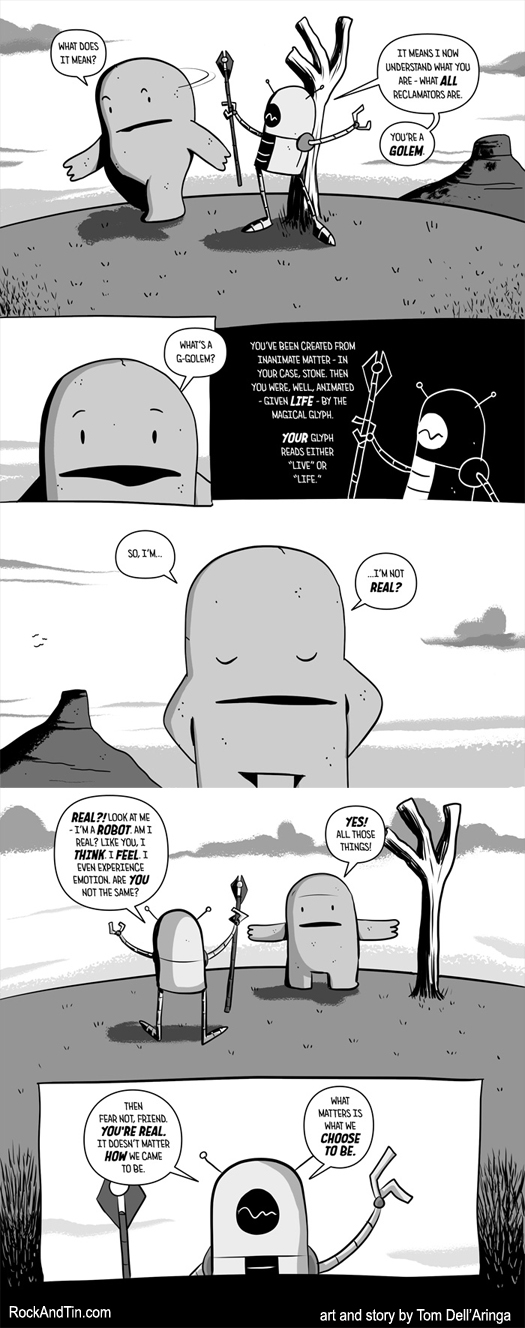

Rock & Tin follows the adventure of Trax the robot (who also goes by Mechmagus, who used to go by The Overseer––I’m choosing to use Trax because I like like it the best) and Peto the Stone Golem (who is given his name by Trax) as they try to save a near-extinct race of robots from obliteration at the hands of the evil Archtinkerer (previously just Tinker), Trax’s brother. The interesting philosophical investigation occurs in the first twenty pages or so as Trax awakens the lost, slumbering golem and they work to establish its identity where it previously had none.

This kind of self-affirming Pinocchio story is a fascinating take on the “what makes me real” question a lot of stories ask––from Toy Story to Descartes. The answer determined by the comic is that not only do you decide who you are, but that the family you choose to make––your friends and allies––are an extension of that as well, a humanistic message that actually hit me pretty hard since it aligns closely with my own ethos. Framing this theme on the conceit of robots and golems extends the metaphor to show that even though we are a biology, birthed and grown over years, we are in many ways just as constructed as machines, albeit a psychological construction rather physical.

What reinforces the need for not only self-identification but also self-reflection is the names of the characters, which is genius (if a bit cumbersome as a few characters have multiple names). The aforementioned main characters (there is a large cast to this book, but these three are the core of the story) have names that are all verbs. Trax is easily “tracks” which is an action, of moving forward specifically with the intent of following something. “Peto” is defined in the narrative, but is Latin for “to seek after,” which emphasizes the parallel journey with Trax. “Tinker” is pretty clear, but also falls in line with the naming schema of the other main characters. But this adds a layer onto the theme of exploring identity. Who you are is more than just a definition, it is an action; more specifically, identity is a forward momentum––something to “seek”––the act of which builds who you are and is something which you can continually change, modify, or refine (i.e., tinker). This level of thought really shows the thoroughness of the author who clearly didn’t really put pen to paper until everything, from top to bottom, was clearly and definitively thought out and is amazing to see unfold.

If there is anything really to criticize about the book it is that Dell’Aringa’s pride for the world he has created eventually overshadows what Rock & Tin is trying to say. As clever and touching as this theme is (especially in this tech-forward age) much of this discourse isn’t maintained past the first forty pages or so, which can cause a schism in the reading experience. As approachable and patient as the beginning of the comic is, it ends quickly, pushing plot and characters into their places to make quite a grand finale as the events of the past––hundreds of years in the making––literally collide with the present and as a result the reader sees how Dell’Aringa intricately worked out every aspect of this society, history, geography, and story. He has built an impressive world for this story and it shows, but there were some spots where the theme of identity and choice could have been more solidly woven back in for a more poignant finale.

It’s hard not to focus on this tension if only because I also read the print version of the story, which emphasizes the world-building rather than the message. The book––from which this overview is based––was the result of a very successful Kickstarter campaign (again, full disclosure: I was a backer) which yielded an absolutely beautiful book. Packed with extra content, the book shows the tremendous amount of thought that went into creating the loping hills that these characters dart around: an illustrated prose story as a prologue, end notes full of developmental sketches and commentary, and two short comics surround the Rock & Tin comic proper and do a lot to build outwards from the relatively small piece of world seen in the story itself. Because of that, however, the book seems to celebrate more of how thoroughly this world has been executed rather than what the story is trying to say.

However, these criticisms are digressions; when placed next to a majority of stories––both all-ages and not––being released by major publishers today, Rock & Tin is a wonderful, thoughtful, and fun book that deserves as much attention as it can garner. Despite being years in the making and his second complete story, Dell’Aringa is still at the start of his game and as he moves forward with his comic work (his next book is already in development) there is no doubt that as a builder, artist, and storyteller his talents will edge ever closer toward the very stars where his stories are set.

Wow, wonderful analysis of the story, Daniel! I think your criticisms are spot on, too – and those are things that I felt, too. But thank you for the kind words and taking time to do this. I also see us as the “same class” that got started about the same time. Long John looks good, keep it up!

No problem at all. It’s all part of my pedagogical goal of showing all comics have a lot to say no matter the genre or style (we all don’t have to be Chris Ware, Daniel Clowes, or Craig Thompson to make a comic with meaning). I’m glad you thought the review was fair and thanks for making a wonderful book! I can’t wait to see the next one.

Right on, Daniel. Couldn’t agree more. Thanks again.

Thanks again.

Thank you Daniel. Very interesting. Never know what is coming next from you!

Thom

Thanks! It’s fun to keep you on your toes!