The Smoking Gun

A comicker that has been quite influential or, at least, inspirational (since his work is not really a direct influence on Long John) is Doug TenNapel. Though he is now mostly known as an outspoken, passionate, and prolific graphic novelist (and I mean that in the way that I use the term––he does not create a series of single issues that is then collected as a single book, he creates and releases whole books––hence, “graphic novels” as I use the term), he has been quite influential in my demographic even if many of us may not be familiar with his name.

For years he actually worked in the video game industry and it was his creation (from concept to design to animation to voice acting) of the 16-bit era class, Earthworm Jim. Though that game spawned multi-generational sequels, he was only directly involved in the first sequel, and eventually got out of games (mostly) entirely. He has worked all over popular media since then, but his name is probably most often associated today with the world of all-ages graphic novels, most notably: Cardboard, Ghostopolis, Tommysaurus Rex, and Creature Tech.

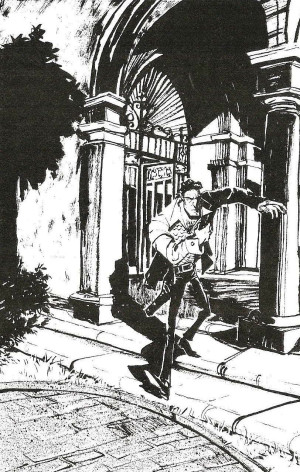

I have a few of his books (he even has a sci-fi western, called Iron West), but I have been most impressed and intrigued by his most adult work, the mobster/alien/crime book, Black Cherry. I am fascinated with it because of its artwork (obviously; it’s basically TenNapel’s Sin City, but it doesn’t share much with that work, either), but just as intriguing is his scathing, exclusionary, and cynical foreword, which actually summarizes TenNaples divisive public personality perfectly. Like him or not as a person who unapologetically expresses his views, his work speaks for itself. More importantly (to me) is that his oeuvre is an example of a single authorial voice in comics––something that doesn’t happen too often. What I mean is that he is as much a writer as he is an artist––but more than that, those two roles are not separate hats. Art is writing and writing is art and, in comics, they can (and, in my opinion, should) be the same thing (this is where I get to be exclusionary). Because of that, he belongs in the same club (dare I say “pantheon”?) as other comickers that have been incredibly influential on me in the last few years: Brandon Graham, Eric Powell, Jeff Lemire, Simon Roy, Hayao Miyazaki, etc.

I bring up TenNapel for a very specific point, however, and it is an artistic one. Amid the above grouping, only two––Jeff Lemire and Doug TenNapel––are very prominently brush inkers (in contrast to those using pens). The others may use brushes, too, but both TenNapel and Lemire’s lines are very clearly made by brushes that it almost defines their style.

I would argue that TenNapel is a more accomplished and dynamic artist than Lemire––probably because of TenNapel’s sheer longevity and work in animation––but what I really like about TenNapel’s art is that he uses the brush expressively, or even impressionistically. His lines are messy and you can see the stray bristles from his surely well-worn brushes, causing wobbly imperfections. Holistically, though, it creates unified tone and look, one that is used especially effectively in Black Cherry, and is so obviously and immediately Doug TenNapel.

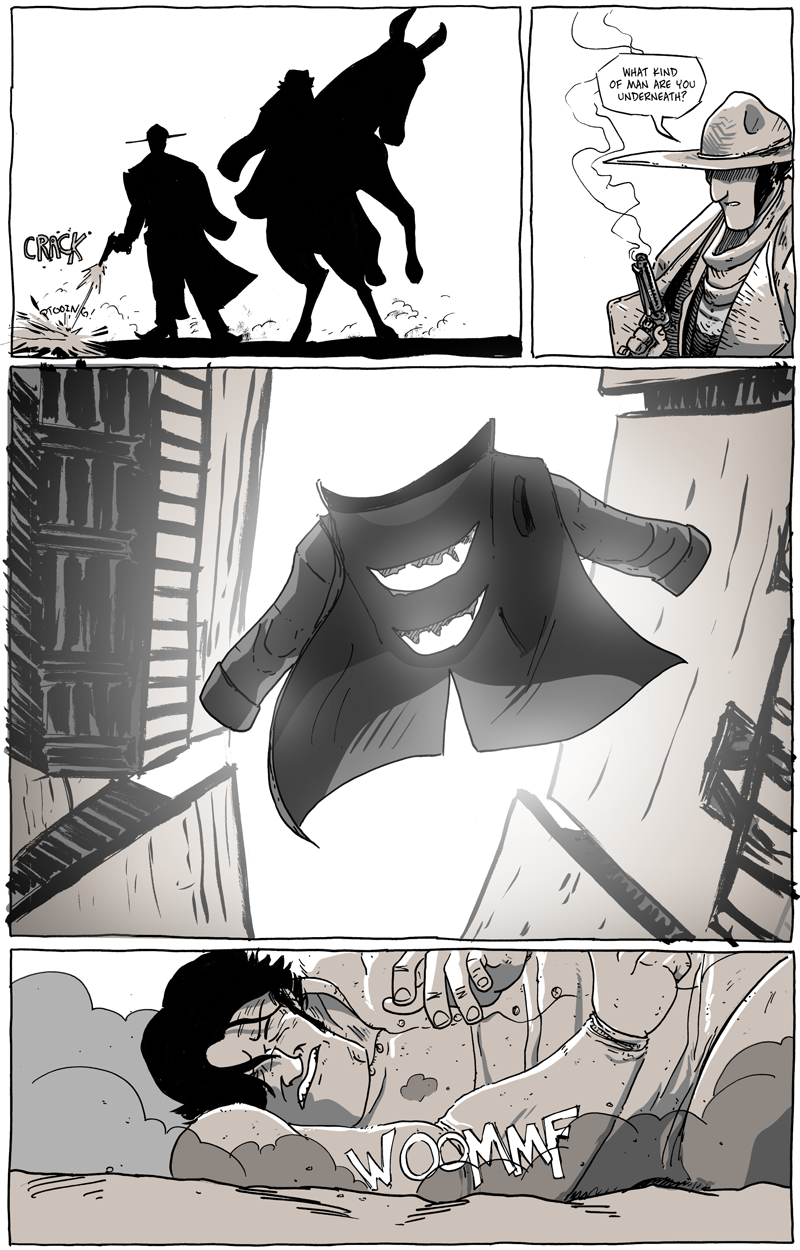

Even though it directly contradicts the “unified look” idea, I occasionally use a brush for Long John (I spoke about it briefly here). I don’t have much training with brushes (or painting, that is…I guess that’s what brushes are usually tools for), so I know I’m not going to get the gorgeous lines of many, more experienced, brush-users. The entire artistic process for Long John relies on the notion that when I sit down to draw it, I want to draw fast. So, when I use a brush, I try to not worry about perfect lines or shapes. I, instead, rely on the TenNapel method––use the brush to make each daub of ink contribute something to the page, the scene, and the story.

Discussion ¬