Hearth and Home

I’ve spoken in many places about things that I like to draw versus things I do not like to draw. By and large, the once-long list of things I do not like to draw has shifted into being a list of things I can draw (and don’t actually mind drawing) but it’s a chore. My previous series, Eben07, had me drawing a lot of difficult stuff––cars, buildings, weapons, planes, etc. In Long John, backgrounds were a bit easier because the Mono Basin is so remote and buildings are handmade with limited resources so things can look a bit more organic, wobbly, and imperfect. All things that are perfect for my style and, most importantly, my ability.

That being said, I went ahead and made it tough on myself by requiring shots of entire towns and complicated, fancy (but dilapidated) interiors. However, it was something I kind of figured out and rather than being things I avoided they became things I can competently render for the purposes of the story in Long John.

With all of that under my belt, nothing prepared me for an awful truth: drawing buildings and stuff is a challenge, but nothing is more difficult to draw than ruin.

More specifically, drawing a ruined building, as we have on this page, requires a very different approach than when drawing a shot of a city or a busy street. With the latter, it’s mostly about planning and laying out things like perspective and the relative heights of objects, buildings, and people. After that, it’s mostly about filling in detail. What makes drawing ruined structures difficult is multi-faceted. First, things don’t consistently break down in the same way. A fire breaks down a house differently than an earthquake, which is different than how a house would break down if just ignored over time. Furthermore, a fire won’t break down a house in the same way twice. In a sense, I got overwhelmed a little bit because it felt like there was a lot of science and physics I would have to understand before I drew this burned-down homestead.

Such education, of course, is not needed.

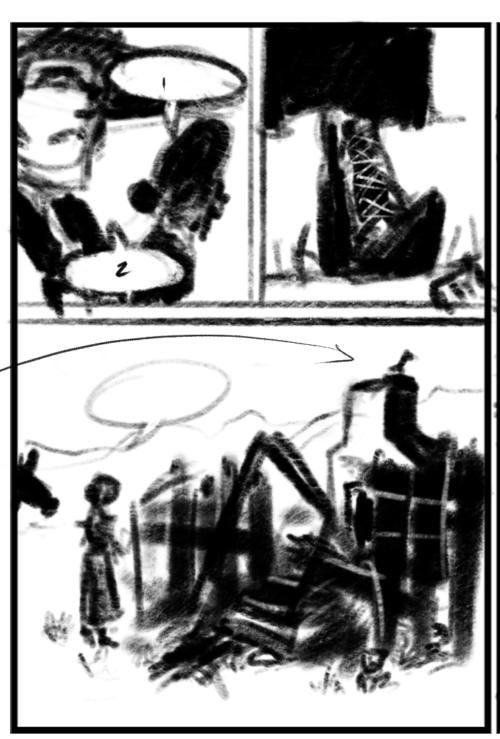

In the thumbnail for this page, I approached panel 3 from a much more architectural, perspective-based angle, which only made things more difficult. (Click for a larger version)

Instead of trying to work out the intricacies of how a fire could burn down this house, it became better to embrace the idea that there are infinite ways for a fire to break down a house. Because of that, there’s no wrong way to draw it.

Instead of using the knowledge and guidance from the architecture-based drawings I’ve become more comfortable with over the last few chapters, I had to approach this much more like drawing a creature because what I have to draw is composition instead of design. In other words, it should look cool more than it is should look correct.

So, what guides panel 3 is shapes and shades rather than precise lines and detail. It’s a carcass on the side of a river, not a structure. Honestly, this more thematic approach is probably the best way to approach drawing architecture overall, too; it’s just a matter––for me––of knowing I can do it right before I can do it well (meaning, expressively). Once I made that leap and embraced the more thematic nature of this ruined homestead, I’m not going to say it became easy; rather, it became something that I had a much larger artistic vocabulary for and found the final result very rewarding.

Discussion ¬