Breaking Up the Set

Revision is everything when it comes to writing.

In practice and in profession, it’s one sentiment that holds true for me. My writing classes revolve around this concept and, although I can stand by all the elements of writing I teach, the idea that revision is the most generative part of the process––where your voice comes through, from which your focus emerges, and where nuance comes into play––sits at the top of the list.

To that end, this part of Chapter 3 looked very different early in the story’s development.

Originally, the Johns were going to make short work of Bishop and his posse and then stand around and talk for, like, six pages. They were going to lay everything out. They would take Long John through what happened the night they betrayed him, why they betrayed him, as well as attempt to calm him down once he learns all the details. For six pages of three dudes standing amid a pile of dead bodies, there was a lot that had to get done. Spurred by the idea that this is the end of the first arc and the conclusion to the first mystery introduced in the comic, I felt that information led to a satisfying conclusion even though there’s more story to tell. Rather than string people along, I wanted people to leave the chapter knowing what happened the night at the lake that led to the start of the book. Naturally, the first instinct is to simply tell the reader what happened.

The problem was that, with the original outcome, I couldn’t see the chapter ending any other way than with the trio getting back together, which wasn’t where I wanted it to go. The point is that it couldn’t go back to how it used to be. The problem was that I was being precious with these characters because I liked them so much.

But––better instincts aside––I wrote the infodump as I planned it and just pushed through to the end of the chapter in my initial layout of the chapter’s plot, because you can’t revise if there’s nothing to work with. Once it was all out and I started approaching scenes with a smaller, sharper scalpel, threads emerged that really helped point me where I needed to go. I found ways to avoid the wall-of-text revelation and found a balance between visuals and dialogue, between what could be said and what needed to be said. At one point I realized that for the dissolution of this group to be really felt, one of them had to die.

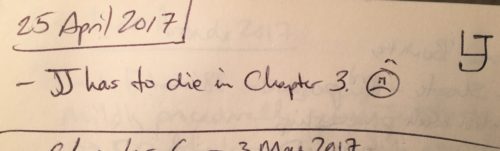

The part that really sealed Juan’s fate was polishing up the opening scene of this chapter. Over the course of a few pages, Juan’s personality and drive––if not explicitly stated––came through much clearer than expected, which brought me to a horrifying realization, which I actually wrote down in my journal:

I push pretty hard against those who say they “let the characters guide the story” because I feel it takes away from the agency of the writer. But the fact remains that these characters aren’t real; they are the product of the writer’s imagination and devotion to their talent. It’s a skill of the writer to make them seem real. In the end, it’s your world and you’re always in control. The key rests with your ability to deviate from bad habits.

This scene is the closest example from my own work that speaks to that idea. However, it wasn’t the characters telling me what to do––just watching the movie in my head, as it were––it was looking at all these pieces I had created, placing them in front me and seeing how they actually fit together––to see the forest for the trees, as the saying goes. I have a natural tendency to lay out a series of points to get me where I need to go, narratively, and just blindly follow that plan––because a plan is a plan and it will get you to your destination. I’ve gotten better at stepping back with each chapter and asking, “okay, I know what I said is going to happen, but what do I have to work with, here, based on what came before? How can I make it better?” Stopping and asking these questions allows me to mold the next step forward instead of just sticking my foot out in front of me and falling forward.

Discussion ¬