Chasing ComicCon

Despite its continuing popularity, many die-hard comic book fans decry the state of the modern San Diego ComicCon as a trophy that has lost its luster, that it is not what it once was and embodies people, products, and values that are alien to the core comic book community. The most popular panels are about movies instead of comic books, as are most of the signings and merchandise booths. At least the big movies at ComicCon are “comic book movies,” though that hasn’t stopped casts of major motion picture releases or television shows––those who don’t have any ties to comics at all––from making appearances, creating long lines, and demanding a panel in the venerable Hall H. The argument boils down to the fact that ComicCon only values the last syllable of its name. While, in many ways, that is absolutely true, in my own San Diego ComicCon experiences, the drift away from comics was what the experience was all about.

I went to the San Diego ComicCon twice, in a row, but it was back when I was a teenager in 1994 and 1995, and I had no idea what to expect. It was a big deal back then, no doubt, but it was a different kind of big deal than it is now, having completely redefined the term in the interim. However, at its heart, the convention operates on the same guiding principles: meet your idols, buy stuff you don’t need, and also get free stuff you don’t need. The first year I went, I only did so for the most obvious goal: to have books signed by my hero, Image Comics founder and penciller extraordinaire, Jim Lee. I was 13 the first year I went, so I certainly had no money to spend on wares––I also was under the self-deprecating ideal that any of the “important” comics that I wanted I would never be able find at a price I could afford. It was only until I got there that I realized the third guiding principal––free stuff––was a thing at all, but that was a bonus and never a reason to drive the six hours every year.

In 1994, the Image Comics revolution was about as big as it could get and I proudly joined that movement, having followed Jim Lee from Marvel’s X-Men to his creator-owned X-Men-adjacent title, WildC.A.T.s. I played the dutiful acolyte, standing in line. It took two hours, and with every step my excitement crested and waned as the optimistic aspect of my personality wrestled with the defeatist. By the time I got to Jim Lee, my psyche was exhausted and all I could do was hand him books with a shaky hand and ask questions, none of which I really remember.

Earlier that year, I had written a letter to his studio––Homage Studios, located in La Jolla, CA, a posh part of San Diego county––asking if I could get a tour of it with a friend as we would be in San Diego visiting relatives. Like sunlight cutting through storm clouds, I received a letter in return from one of the writers at the studio who politely refused my self-invitation but who said they would be at the convention later in the year. A few months later, I received a trading card in the mail in an envelope with a La Jolla return address but no name and no letter explaining what it was or why I was receiving it––the card featured a WildC.A.T.s character over a “foil holograph” background. Taking it as a sacred gift from the comic book powers above, I purchased a hard-shell plastic case in which it still sits fully protected. The card was among the books I brought to have Jim Lee sign, and once the books were out of the way, I pulled out the card, still in its case, and handed it to him, asking why he thought I may have gotten it as I did so.

I wanted desperately for him to reveal that it was akin to Wonka’s golden ticket and it meant that I was chosen from millions for bigger and better things, an heir to be trained for rule…over comics. Instead, Jim Lee did his best to come up with an answer that wasn’t just, “I don’t know,” and, as he did so, fumbled with the card in its hard plastic case. Failing to open it and needing to move things along, with a few flicks of his wrist, he signed the case and handed it back to me and thanked me for stopping by.

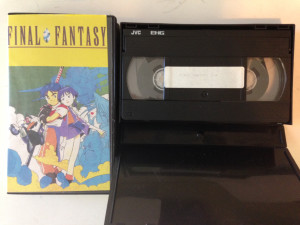

I left the line and was ushered back onto the con floor, holding a small pile of signed books and a very valuable plastic trading card case. After my friend got his stuff signed, we just wandered the floor trying to feel our limbs again. Eventually, we crossed in front of a vendor who had a large television playing a cartoon that I had never seen before. VHS tapes with poorly photocopied covers lined his table. Most of the spines were written in Japanese, but a few titles popped out that caught our attention: Ninja Ryukenden (Ninja Gaiden), Samurai Spirits (Samurai Shodown), Fatal Fury, Final Fantasy: The Legend of the Crystals.

“That Final Fantasy series is a good one,” the heavy-breathing man behind the counter said.

“What is it?” my friend and I asked.

“It’s a cartoon based on Final Fantasy.”

Being rather familiar with the franchise, we asked the most logical question.

“Which one?”

“Which one what?”

“Which Final Fantasy is it based on?”

He paused. “I don’t know,” he said, and that rhetoric was good enough for us (for what it’s worth, it is a loose sequel to the events of Final Fantasy V).

The price was right and we bought a pile of garage-translated tapes, discovering the world of anime in the process. Back then, there was no publicly available anime aside from Akira and a slew of series like Ranma 1/2 or Record of Lodoss War, but they were always rented out or, with regard to series, they never seemed to have complete sets and the only real exposure kids my age had to Japanese animation were the strange Frankensteinian monsters that were Voltron or Robotech. They were, however, awesome. After that first year at ComicCon, however, we had an in. After getting home and consuming all the tapes we purchased––and making copies for each other––the next year was marked by a countdown to a return to ComicCon all with a singular goal in mind: to buy more anime.

Almost as soon as I walked away from Jim Lee’s table clutching my signed books the curtains of comic book fandom closed behind me. I had achieved more than I had ever thought was possible––I had climbed the mountain and returned with tablets marked with the words of god himself (in my teenage eyes). Any further goals I could have crafted for myself as a comic book fan would only be shadow puppets in comparison. In that vacuum, however, ComicCon filled the void. It’s not an encampment to keep the heathens out. It is a place to gather and see what else our faith can consume, which is what makes the modern ComicCon so impressive––our faith has consumed the entire world.

ComicCon may have grown and changed from what it was in the past; it may have even become an event that we feel doesn’t welcome us anymore. But––back in the fabled “good old days”––I took from ComicCon what I wanted, but it was also there for me when I needed it, and now I see that the whole world wants what I had because they realize that the heart of ComicCon is not comics, or movies, or television shows, or toys––it’s about getting what you want and finding what you need, even if you didn’t know you were looking for it . At its best, ComicCon is a transformative experience so many people are chasing because that’s what they heard it could be, and they heard that from people like us. I can’t argue with that, and I can’t discourage it even if it’s not somewhere I want to be anymore.

Discussion ¬